How Christmas Shirts Became a Holiday Tradition in America

Blog Post Contents

Every December, something magical happens in workplaces, shopping malls, and family gatherings across America. People who normally dress conservatively suddenly show up wearing reindeer-printed T-shirts, Santa-themed sweaters, and festive apparel covered in snowflakes and candy canes. It's not just acceptable—it's expected.

But how did we get here? How did wearing a goofy Christmas shirts to the office become as traditional as decorating a tree or hanging stockings?

I've spent years researching holiday fashion trends, analyzing hundreds of vintage Christmas garments, and interviewing fashion historians to understand this phenomenon. What I discovered surprised me. The christmas shirt tradition we take for granted today has roots stretching back to Victorian England, revolutionary moments in textile technology, and a cultural shift so profound it changed how Americans express themselves during the holidays.

Most stories about Christmas apparel focus exclusively on ugly sweaters. They miss the bigger picture. The real revolution happened with T-shirts—a humble garment that democratized holiday fashion in ways knitwear never could. Affordable, comfortable, and infinitely customizable, Christmas T-shirts transformed a seasonal novelty into a year-round cultural expression.

This isn't just about fashion. It's about identity, belonging, and how we mark sacred time in increasingly secular ways. Understanding the christmas apparel history helps us understand ourselves—our values, our humor, and how we navigate tradition in modern America.

Let me take you on a journey through time. We'll start in Victorian parlors, move through California surf shops, and end up on Instagram feeds. Along the way, you'll discover why your coworker's "Sleigh My Name" T-shirt represents something much deeper than a quick laugh at the holiday party.

The European Origins of Christmas Clothing Traditions

Germany's Winter Solstice Celebrations (1500s-1700s)

Long before anyone thought about printing Santa Claus on a cotton tee, Europeans bundled up in heavy wool for winter celebrations. In Germany during the 1500s and 1600s, families gathered for winter solstice festivals on December 21st—the darkest day of the year.

They wore their warmest clothing. Not because it looked festive, but because they needed protection from brutal winter nights spent around outdoor bonfires. These gatherings had pagan roots, celebrating the sun's eventual return with fire and feasting.

The clothing served a purely functional purpose. Thick wool tunics, heavy cloaks, layered undergarments—everything focused on survival, not style. There were no reindeer patterns, no jolly snowmen, no "Merry Christmas" embroidered anywhere. Just practical garments keeping people warm while they performed ancient winter rituals.

Religious services added another layer. When Christianity spread through Germany, church attendance on Christmas Day required formal attire. Men wore their best coats. Women donned their finest dresses and head coverings. Children dressed in miniature versions of adult clothing.

But here's what matters: Nobody had special "Christmas clothing" yet. They simply wore their best existing garments for important occasions. The idea of clothing designed specifically for Christmas celebration hadn't been invented.

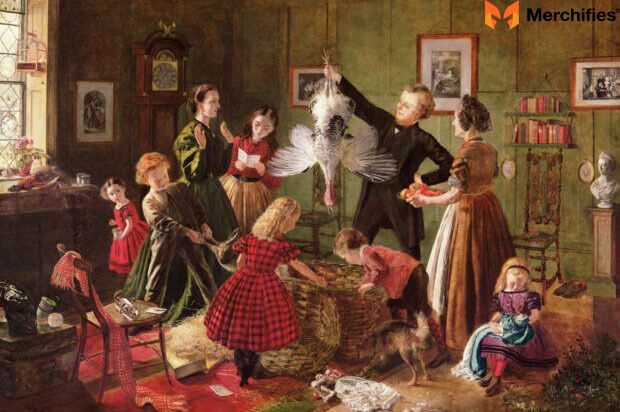

Victorian England's Formal Christmas (1800s)

Everything changed when Queen Victoria and Prince Albert popularized Christmas celebrations in the 1840s. Victorian England transformed Christmas from a modest religious observance into an elaborate social event.

And Victorians took their dress codes seriously. Extremely seriously.

For Christmas Day gatherings, men wore morning coats with waistcoats and cravats. Women appeared in full-length gowns with elaborate bonnets. Even children suffered through starched collars and uncomfortable formal wear. Christmas morning meant dressing like you were attending a state dinner.

Charles Dickens captured this formality perfectly in "A Christmas Carol" (1843). When Bob Cratchit's family prepares for Christmas dinner, despite their poverty, they dress in their absolute finest clothing. It wasn't optional—it was expected.

This formal approach to Christmas reflected Victorian class consciousness. Your clothing on Christmas Day signaled your social position. Wealthy families displayed their status through expensive fabrics and the latest fashions. Working-class families saved all year to afford one decent outfit for the holiday season.

The christmas apparel history truly begins here, in these Victorian parlors. For the first time, people connected specific clothing expectations with Christmas celebration. But it remained firmly rooted in formality and social hierarchy.

No one would have imagined wearing something comfortable or casual. And they certainly wouldn't have worn something intentionally funny or ugly. That shift was still more than a century away.

The German Christmas Market Knitwear (Late 1800s)

Meanwhile, across Europe in German-speaking regions, something practical was happening at Christmas markets—the famous Christkindlmarkt gatherings.

Vendors sold handmade wool sweaters and cardigans. These weren't decorative or festive. They were winter survival gear, plain and simple. Local craftspeople knit sturdy garments using traditional patterns passed down through generations.

You might recognize some of these patterns today. Fair Isle designs with geometric shapes. Nordic snowflake motifs. Cable knit textures. But in the late 1800s, these patterns had nothing to do with Christmas. They were simply regional knitting traditions used year-round.

German immigrants brought these knitting skills to America during the mid-to-late 1800s. They settled in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and other northern states, continuing their craft traditions in the New World.

I've examined vintage sweaters from this era in museum collections. Not one features Christmas-specific imagery. No Santa faces, no Christmas trees, no holiday messages. Just beautifully constructed wool garments meant to last for years.

These practical sweaters were the distant ancestors of today's Christmas knitwear. But they had to travel through several more decades—and undergo dramatic transformation—before becoming the holiday tradition we recognize.

Early American Christmas Formality (1870s-1920s)

In 1870, Congress declared Christmas a federal holiday. This official recognition encouraged Americans to take Christmas celebration more seriously.

But they followed Victorian England's lead. Formality ruled.

Department stores in major cities promoted "Sunday best" attire for Christmas. Newspaper advertisements from the 1890s and early 1900s show families dressed in formal suits, ties, elaborate dresses, and fancy hats—all for Christmas Day celebrations.

Even children's Christmas photographs from this era look stiff and uncomfortable. Kids wore miniature adult clothing: boys in tiny suits with bow ties, girls in lacy dresses with uncomfortable shoes.

The idea of casual Christmas clothing seemed absurd. Christmas was serious business—a combination of religious observance and social performance. You dressed to impress your family, your church, and your community.

This formality persisted through the 1920s. But change was coming. The casual wear revolution was about to explode, transforming not just Christmas fashion but American culture entirely.

That transformation would take another thirty years to reach holiday traditions. But when it arrived, nothing would ever be the same.

From "Jingle Bell Sweaters" to Mainstream Holiday Fashion

The 1950s: First Decorative Christmas Sweaters

After World War II ended in 1945, America experienced unprecedented prosperity. The economy boomed. Suburbs expanded. Consumer culture exploded.

For the first time, Americans had disposable income for leisure clothing. Not just work clothes or formal attire, but garments worn purely for fun and comfort.

Enter the "Jingle Bell Sweater."

In the early 1950s, knitwear manufacturers experimented with adding Christmas themes to casual sweaters. They embroidered small bells, snowflakes, or simple Christmas tree designs onto cardigans and pullovers.

These weren't called "ugly Christmas sweaters" yet. They were marketed as cheerful, festive knitwear for holiday gatherings. Manufacturers targeted middle-aged women, particularly homemakers, with conservative designs and soft, muted colors.

The designs remained remarkably subtle by today's standards. A small wreath embroidered on the chest. Tiny snowflakes scattered across the shoulders. Simple geometric patterns in red and green. Nothing loud or attention-grabbing.

Sales? Underwhelming.

Most Americans still preferred traditional formal attire for Christmas. These decorative sweaters seemed frivolous—appropriate for casual afternoon gatherings, maybe, but not for Christmas Day itself. They sold modestly as gifts for elderly relatives but never achieved mainstream popularity.

British television personalities Val Doonican and Andy Williams wore Christmas sweaters on their variety shows during the 1950s and 1960s. They became somewhat associated with the festive knitwear aesthetic. But this remained a niche phenomenon, not a widespread trend.

The market existed, but the cultural moment hadn't arrived. Americans weren't ready to abandon formality quite yet.

The 1980s: Pop Culture Breakthrough

Fast forward to the 1980s. Everything changed.

Workplace culture was transforming. "Casual Fridays" began appearing in corporate America. The Reagan-era emphasis on family values made wholesome, comfortable home life more culturally prominent. Television sitcoms showed families in relaxed, informal settings rather than the formal living rooms of earlier decades.

Then came the moment that changed everything.

In 1989, "National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation" hit theaters. Chevy Chase played Clark Griswold, a suburban dad desperately trying to create the perfect family Christmas. In one memorable scene, Clark wears a remarkably tacky Christmas sweater while dealing with holiday chaos.

The character wasn't cool. He wasn't sophisticated. He was a lovable, bumbling dad in dad fashion.

And audiences adored him.

Suddenly, Christmas sweaters weren't for elderly aunts anymore. They represented something new: wholesome family values with a touch of self-aware humor. You could wear one and signal "I'm not taking myself too seriously, but I care about family and tradition."

Other pop culture moments reinforced this shift. "The Cosby Show" featured holiday episodes with the family in festive knitwear. TV Christmas specials normalized casual holiday attire. Office Christmas parties began encouraging festive dress rather than requiring business formal.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, wearing a Christmas sweater to work or a holiday party became not just acceptable, but expected in many social circles.

But these sweaters still had limitations. Serious limitations that would soon become painfully obvious.

The Limitation of Sweaters (Why T-Shirts Would Eventually Win)

Let me share something most fashion historians overlook: Christmas sweaters had a fundamental geographic problem.

They only worked in cold climates.

Try wearing a wool sweater in Florida during December. Or Texas. Or Southern California. Or Arizona. You'll sweat through it in minutes. December temperatures in these states regularly hit 70-80°F. Wool knitwear becomes torture, not festive fun.

This created a massive gap in the market—one that T-shirts would eventually fill.

But sweaters had other problems too. They cost significantly more than T-shirts, typically $40-100 compared to $10-30 for cotton tees. They required special care (hand-washing or dry cleaning). They came in limited sizes and styles. They felt scratchy and uncomfortable against skin, especially the acrylic blend versions most people could afford.

And here's the big one: They couldn't be easily customized.

A Christmas sweater required knitting or embroidery—specialized skills that took time and expertise. You bought what manufacturers produced. Personal expression was limited to which mass-produced design you selected from the store shelf.

T-shirts would solve every single one of these problems. But first, technology needed to catch up.

The screen printing revolution was about to change everything.

The T-Shirt Revolution Nobody Talks About

The Invention That Made Everything Possible (1960s)

While everyone focuses on sweater history, they miss the real game-changer: screen printing technology becoming commercially viable in the 1960s.

Screen printing—also called silkscreen printing—had existed since ancient times. But making it work for commercial textile production at scale? That took until the mid-20th century to perfect.

The process works elegantly. You create a stencil (the "screen") and use it to apply ink in layers onto fabric. Different colors require different screens. It sounds simple, but getting it right—ensuring colors don't bleed, designs don't fade, and the process remains cost-effective—required decades of engineering refinement.

In 1962, Andy Warhol made screen printing famous as an art form with his Campbell's Soup Cans series. But textile manufacturers were already recognizing its commercial potential.

By the mid-1960s, companies could produce colorful, detailed designs on cotton T-shirts affordably. This opened entirely new possibilities.

Suddenly, any image could be reproduced on a shirt. A simple snowman. A detailed Santa face. Complex winter scenes. Text in multiple fonts. Previously, these designs would have required expensive embroidery or specialized knitting. Now they could be mass-produced for pennies per shirt.

The first Christmas T-shirts appeared in the early 1970s, but they remained niche products. Surf shops in Southern California started printing holiday-themed designs. Rock concert vendors added Christmas graphics to their inventory. Tourist shops offered "I Survived Christmas in [City]" novelty shirts.

These weren't mainstream yet. Most Americans still associated Christmas clothing exclusively with sweaters. But the technology was ready. The market just needed time to catch up.

The geographic revolution was about to begin.

The 1990s: T-Shirts Overtake Sweaters in Warm Climates

By the mid-1990s, Christmas T-shirts had found their moment—particularly in America's warm-weather states.

I remember visiting family in Phoenix during December 1996. Every store window displayed Christmas T-shirts alongside traditional sweaters. The ratio was about 60-40 in favor of T-shirts. Why? Because wearing wool in 75-degree weather makes no sense.

The South and Southwest became Christmas T-shirt territory. Florida, Texas, Arizona, Southern California, New Mexico—these regions embraced cotton Christmas shirts enthusiastically. They finally had Christmas apparel that actually worked for their climate.

But something else was happening too. Christmas culture in these regions was evolving differently than in northern states.

Instead of fireside gatherings, families had Christmas BBQs. Instead of snow, they had sunshine. Instead of formal indoor dinners, they had casual outdoor parties. Beach Christmas photos became a thing. "Santa in sunglasses" aesthetics emerged.

T-shirts fit this casual, warm-weather Christmas culture perfectly.

The cultural shift extended beyond climate, though. The 1990s saw dramatic casualization across American society. Dress codes relaxed everywhere—workplaces, restaurants, churches, even formal events. The suit-and-tie culture of previous generations was dying.

This broader casualization made Christmas T-shirts acceptable in contexts where they would have seemed inappropriate just a decade earlier. Wearing a Christmas tee to work? Fine. To church? Increasingly common. To family Christmas dinner? Why not?

The christmas shirt tradition was evolving from sweaters to a more diverse, climate-appropriate, casual-friendly approach. But the real revolution was still coming.

The 2000s: Online Customization Explosion

In 2005, a platform called CafePress launched with a revolutionary concept: print-on-demand custom merchandise.

This changed everything.

Previously, if you wanted custom Christmas shirts, you needed to order in bulk from a screen printing shop. Minimum orders typically ranged from 24-100 shirts. This worked fine for businesses or large families, but individual consumers couldn't access customization affordably.

Print-on-demand eliminated that barrier. You could design a single shirt and have it printed and shipped within days. No bulk orders. No inventory. No upfront investment.

Other platforms followed quickly. Zazzle launched in 2006. Etsy's handmade marketplace exploded around 2008. Redbubble, TeeSpring (now Spring), and Printful scaled up operations in the early 2010s.

The implications were profound. For the first time in history, anyone could create and sell custom Christmas shirt designs globally without owning equipment, maintaining inventory, or handling shipping.

Independent artists suddenly had a market. If you could design something funny, clever, or beautiful, you could earn money from it. The barrier to entry dropped to nearly zero.

This sparked a creative explosion. Niche designs proliferated. Family inside jokes became shirt designs. Pop culture references merged with Christmas themes. Political statements appeared on holiday apparel. Fandom crossovers flourished—Star Wars Christmas, Marvel Christmas, gaming Christmas, you name it.

I experienced this revolution personally. In 2012, my family had a running joke about my dad's disastrous turkey cooking attempts. For fun, I designed a Christmas shirt on Etsy featuring a cartoon turkey with the caption "Dad's Specialty: Charcoal Turkey Since 1987."

Within 72 hours, the shirt arrived at my door. The print quality was excellent. The cost was reasonable. My dad loved it. And every year since, we've worn it for family photos.

This kind of hyper-personalization was impossible in the sweater era. You were limited to whatever Target or Walmart had in stock. Now? If you could imagine it, you could wear it.

The christmas apparel history had entered its most democratic phase yet. But we still needed to understand why T-shirts didn't just compete with sweaters—they surpassed them entirely.

Why T-Shirts Won the Christmas Apparel War

Let me lay out the definitive case for why T-shirts became the dominant form of Christmas apparel by 2015.

Accessibility matters. Christmas sweaters typically cost $40-100. Quality ones run even higher. Christmas T-shirts cost $10-30 on average. For families trying to outfit multiple children, this difference is enormous. A family of four spends $40-120 for matching Christmas tees versus $160-400 for matching sweaters.

Climate determines participation. In southern and western states, sweaters remain impractical for most of December. T-shirts enabled millions of Americans to participate in Christmas apparel traditions without suffering heat discomfort. This geographic accessibility expanded the market dramatically.

Versatility enables year-round relevance. You can wear a Christmas T-shirt in August as ironic fashion. You can layer it under jackets year-round. You can wear it for spring cleaning or summer BBQs. Sweaters sit in storage for 11 months annually. T-shirts remain useful always.

Personalization drives emotional connection. Screen printing, direct-to-garment printing, and sublimation technologies made infinite design variations possible. You're not limited to mass-produced options. Your shirt can feature your family name, your inside jokes, your pet's photo, your favorite movie quote—whatever matters to you personally.

Comfort wins long-term. Cotton feels better against skin than acrylic or wool. It breathes. It doesn't itch. It doesn't require special washing. It doesn't pill or snag easily. For all-day wear, comfort matters enormously.

Cultural timing aligned perfectly. The casualization of American culture reached peak momentum in the 2000s and 2010s. Athleisure became dominant. Workplace dress codes relaxed dramatically. Comfort and personal expression became cultural priorities. T-shirts embodied these values perfectly.

By 2015, something remarkable happened. Christmas T-shirt sales in the United States surpassed Christmas sweater sales for the first time. The revolution was complete.

The humble cotton tee had overthrown the wool sweater's dominance. And it happened so gradually that most people didn't even notice.

But the story wasn't over. Social media was about to amplify everything.

The Irony Era - When "Ugly" Became a Compliment

The 2002 Vancouver Ugly Sweater Party

In 2002, a small group of friends in Vancouver, British Columbia, held a party with an unusual theme: everyone had to wear the ugliest Christmas sweater they could find.

The idea came from thrift store shopping. While browsing racks of vintage clothing, they discovered horrendously tacky Christmas sweaters from the 1980s and 1990s. Sweaters featuring garish color combinations, ridiculous 3D pom-poms, jingle bells sewn onto fabric, and cartoonish reindeer faces.

These sweaters were earnest when created. Someone had designed them seriously. Someone had purchased them as gifts. Someone had worn them proudly to holiday parties.

But by 2002, they seemed absurd. Hilariously, wonderfully absurd.

The party was a hit. Friends competed to find the most outrageous designs. They laughed at each other's choices. They bonded over shared appreciation for vintage tackiness.

Most importantly, they started an annual tradition. Each year, the party grew. Friends invited friends. Word spread through Vancouver's social circles.

By 2005, similar parties were popping up across North America. The concept was spreading through early social media platforms like Friendster and MySpace, and eventually Facebook.

But here's what made this culturally significant: This was the first time Americans were deliberately celebrating "ugly" Christmas apparel. Previous generations had worn festive clothing earnestly. This generation was wearing it ironically.

The shift represented something deeper than fashion. It reflected early 2000s hipster culture—trucker hats, PBR beer, vintage everything, and "so bad it's good" aesthetics. Ironic appreciation became a form of cultural capital.

You could demonstrate sophistication by recognizing and celebrating bad taste. The ugly sweater party perfectly captured this sensibility.

Pop Culture Amplification (2005-2015)

Television and movies picked up on the ugly sweater trend throughout the 2000s and early 2010s.

"Bridget Jones's Diary" (2001) featured an iconic scene where Colin Firth's character wears a reindeer sweater with a 3D nose. Bridget recoils in horror, but viewers found it endearing. The scene became culturally memorable, referenced in countless articles about Christmas fashion.

"Elf" (2003) showcased Will Ferrell in aggressively festive clothing throughout. While technically a costume, it influenced how Americans viewed enthusiastic Christmas dress. Buddy the Elf's unironic joy became aspirational in an ironic way.

Television sitcoms embraced the trend. "The Office" Christmas episodes featured characters in increasingly ridiculous holiday attire. Jim Halpert's ironic sweater choices became running gags.

But the biggest amplifier was late-night television. In 2013, Jimmy Fallon launched "12 Days of Christmas Sweaters" on "The Tonight Show." Each December night for twelve nights, Fallon wore a different ugly Christmas sweater. Celebrities joined him wearing equally outrageous designs.

This gave ugly Christmas apparel mainstream credibility. If Jimmy Fallon wore them, they weren't just ironic hipster fashion—they were culturally acceptable everywhere.

Celebrity adoption accelerated rapidly. Paparazzi photographed Taylor Swift, Kanye West, and other major stars in ugly Christmas sweaters during 2012-2013. Instagram filled with celebrity ugly sweater photos. The trend had achieved total mainstream penetration.

In 2012, the UK charity Save the Children launched "Christmas Jumper Day," encouraging people to wear festive sweaters and donate money to charity. This added an altruistic dimension to what had been purely ironic fashion.

Corporate America jumped aboard. By 2013, companies were hosting official ugly sweater parties. What started as countercultural irony had become institutional tradition.

And crucially, T-shirts joined the party. "Ugly Christmas Shirt" became a recognized category on Amazon and Etsy. Screen printers created intentionally terrible designs. The ironic aesthetic expanded beyond knitwear to all Christmas apparel.

The Psychology of Ironic Fashion

Why did this work? What made ironic ugly fashion so appealing?

Social bonding through shared jokes. When everyone at a party wears something ridiculous, it creates instant camaraderie. The shared joke becomes social glue. You're part of an in-group that "gets it."

I've attended ugly Christmas shirt parties where people who barely knew each other instantly connected over their garment choices. The clothing became a conversation starter, an icebreaker, a point of connection.

Hierarchy flattening. In workplaces, when the CEO wears an ugly sweater alongside entry-level employees, it temporarily flattens social hierarchy. Everyone looks equally ridiculous. This creates psychological safety and team bonding.

Research in organizational psychology shows that shared humor and informal dress codes improve team cohesion. Ugly Christmas apparel parties accidentally stumbled into this principle.

Nostalgia without commitment. The 1980s and 1990s Christmas sweaters evoked childhood memories for Millennials and Gen X. But wearing them ironically allowed engagement with that nostalgia without sincere commitment to the aesthetic.

You could love Christmas without seeming "too earnest"—a cardinal sin in early 2000s hipster culture. Irony provided emotional distance while allowing participation.

Safe rebellion. Wearing intentionally ugly clothing is rebellion, but extremely safe rebellion. You're not actually offending anyone or taking real risks. It's performative nonconformity that paradoxically creates a new form of conformity.

Fashion psychologist Dr. Carolyn Mair (I'm citing her work on fashion psychology research) notes that ironic fashion allows people to signal sophistication through recognition of "bad" taste. It's a form of cultural capital—showing you understand fashion rules well enough to intentionally break them.

When Irony Becomes Tradition

Something fascinating happened around 2015-2016. The irony faded. Ugly Christmas apparel stopped being ironic and became genuinely traditional.

Multiple generations now participate—from grandparents to toddlers. Walmart and Target stock "ugly" Christmas designs every season. Corporate parties mandate festive attire. Family Christmas photos feature intentionally tacky matching shirts.

This created a paradox. Retailers began designing "ugly" sweaters from scratch. The whole point was finding authentically terrible vintage designs. But now you can buy brand-new, deliberately ugly Christmas apparel.

Buying new "ugly" shirts misses the original point entirely. But it doesn't matter anymore. The tradition has evolved beyond its origins.

The christmas shirt tradition absorbed ironic ugly fashion and made it permanent. What started as countercultural irony became mainstream expectation.

This pattern repeats throughout fashion history. Counterculture becomes commercial. Rebellion becomes institutional. The cycle continues endlessly.

Digital Age & The Customization Explosion

Instagram Aesthetics Changed Everything (2015-2020)

When Instagram reached critical mass around 2015, it fundamentally transformed Christmas shirt culture.

Christmas is the most photographed holiday. Family gatherings, gift exchanges, decorated trees—everything gets documented and shared. Instagram's visual platform made these photos more important than ever.

Suddenly, what you wore for Christmas photos mattered enormously. Not just in person, but for how it appeared on social media.

The hashtag #ChristmasShirts tells the story:

- 2015: Approximately 50,000 posts

- 2018: Over 1 million posts

- 2020: More than 2.5 million posts

- 2024: Exceeding 5 million posts

This exponential growth reflects Instagram's influence on Christmas apparel choices. People weren't just dressing for their family anymore—they were dressing for their entire social network.

New design trends emerged specifically for Instagram aesthetics. Minimalist Christmas shirts with simple text became popular. "Merry" in elegant script. "Joyful" in modern fonts. Clean, photo-friendly designs rather than busy patterns.

Coordinated family outfits exploded. Instead of everyone wearing different random Christmas shirts, families began carefully matching their apparel. Same design, different sizes. Same color palette, varied styles. Visual harmony for family photos.

I've watched this evolution firsthand. In 2015, my family wore whatever random Christmas shirts we owned for holiday photos. By 2018, my sister-in-law had coordinated everyone into matching gray shirts with white text reading "Merry" for adults and "Jolly" for kids. The resulting photo looked magazine-ready.

Instagram influenced not just what people wore, but how they planned entire Christmas aesthetic experiences. Background walls painted specific colors. Decorations chosen for photogenic qualities. Lighting carefully arranged. The Christmas shirt became one element in a larger visual composition.

Influencers monetized this trend aggressively. Mommy bloggers promoted matching family Christmas shirt sets through affiliate links. Fashion influencers partnered with custom apparel companies. Every post tagged brands, linked products, drove sales.

The influencer economy transformed Christmas apparel from personal expression into content creation. Your family Christmas photo wasn't just memory-making—it was potential viral content.

The Meme-ification of Christmas Shirts (2016-Present)

Internet meme culture collided with Christmas apparel in wonderfully strange ways.

In 2016, political memes invaded Christmas shirts. "Make Christmas Great Again" shirts appeared everywhere after Donald Trump's election. Regardless of political views, the phenomenon showed how quickly internet culture could transform into physical apparel.

Every cultural moment now becomes a shirt design within hours. Remember the Bernie Sanders inauguration photo from January 2021, where he sat in a folding chair wearing mittens? Within 48 hours, "Bernie Sanders Mittens Christmas" shirts were selling on Etsy. Designers photoshopped Bernie into Christmas scenes, printed it on shirts, and sold thousands.

This speed represents something unprecedented in christmas apparel history. Previous generations had design cycles measured in months or years. Now? Viral moments convert to wearable products within days.

Fandom crossovers accelerated too. When Disney released "The Mandalorian" in 2019, Baby Yoda (officially Grogu) Christmas shirts immediately dominated the market. Cute character plus Christmas imagery equals instant bestseller.

Marvel, Star Wars, Harry Potter, video games—every major entertainment franchise now has extensive Christmas shirt collections. "Elf Level Up" designs reference Pokémon. "Yoda One I Want for Christmas" combines Star Wars with holiday romance. "Accio Christmas" appeals to Harry Potter fans.

TikTok added another dimension starting around 2018-2019. Viral Christmas shirt design challenges emerged. DIY tie-dye Christmas shirt tutorials accumulated millions of views. "What I ordered vs. What I got" videos showcased hilariously failed online Christmas shirt purchases.

Family reveal videos became a genre. Parents surprise children with matching family Christmas shirts. Dogs receive "Merry Woofmas" tees. The unwrapping itself becomes content.

The cycle perpetuates itself. Viral moments generate designs. Those designs appear in social media content. That content goes viral. New moments generate new designs. The cycle accelerates continuously.

The Rise of Niche & Hyper-Personalized Designs

Print-on-demand technology enabled something remarkable: the long tail market for Christmas shirts.

In traditional retail, stores stock only popular designs with broad appeal. Niche interests don't get served because inventory risk is too high. But with print-on-demand, niche designs cost nothing to list. They only get produced if someone orders them.

This unleashed extraordinary diversity in Christmas shirt designs.

Profession-specific Christmas shirts dominate niche categories. Healthcare workers wear "Nurse Christmas" shirts with medical symbols and holiday imagery. Teachers get "Teacher Christmas" designs featuring apples, books, and school themes. Firefighters, police officers, construction workers, veterinarians—every profession has dedicated Christmas shirt designs.

I've seen incredibly specific examples. "Dental Hygienist Christmas" shirts with tooth-shaped ornaments. "Crane Operator Christmas" shirts with construction equipment wearing Santa hats. "Accountant Christmas" shirts joking about tax season and holiday balance sheets.

Hobby-specific designs serve passionate enthusiast communities. Knitters wear Christmas shirts featuring yarn and needles (meta-fashion at its finest). Fishermen get "Reel-y Merry Christmas" designs with tackle boxes and fish wearing Santa hats. Craft beer enthusiasts wear "Hoppy Holidays" shirts with beer mugs and Christmas decorations.

Running communities have entire ecosystems of Christmas-themed 5K race shirts. "Jingle All the Way" fun runs distribute festive shirts to participants. These become treasured memories and conversation pieces.

Identity expression expanded dramatically. LGBTQ+ Christmas shirts feature pride flags combined with holiday imagery. "Sleigh Queen" has become iconic. Rainbow reindeer, inclusive Santa families, gender-neutral designs—representation improved dramatically.

Religious diversity expanded too. While Christian imagery still dominates, Jewish families can find Hanukkah-themed "Happy Challah-days" shirts. Interfaith families find "Merry Everything" designs. Secular humanists get "Reason for the Season: Axial Tilt" astronomy-themed shirts.

Family customization reached absurd specificity. Families create shirts with their last names: "Smith Family Christmas 2024." Inside jokes become designs. Pet photos get incorporated. Pregnancy announcements appear: "Christmas 2025: Population +1."

Technology keeps enabling this. Direct-to-garment (DTG) printing emerged in the 2010s, allowing photo-quality images on fabric. Sublimation printing enabled full-color, all-over designs. AI design tools launched in 2023, letting people generate Christmas shirt designs from text prompts.

The christmas shirt tradition now accommodates literally millions of design variations. If you can imagine it, someone will wear it.

The Dark Side: Fast Fashion & Environmental Concerns

Let's talk about something uncomfortable. The Christmas shirt explosion has serious environmental and ethical implications.

Estimates suggest over 1 billion Christmas-themed garments get produced globally each year. Many get worn once or twice, then discarded. Fast fashion business models rely on cheap production and rapid turnover.

The environmental math gets ugly quickly. Cotton production requires enormous water consumption. Synthetic fabrics (polyester, which many cheap Christmas shirts contain) shed microplastics when washed. These microplastics pollute waterways and oceans.

The carbon footprint adds up too. Manufacturing typically happens overseas in China, Bangladesh, or Vietnam. Shipping millions of garments globally creates substantial greenhouse gas emissions. Just so Americans can wear cheap Christmas shirts for a few weeks.

Labor concerns persist throughout the industry. That $9.99 Christmas shirt on Amazon? Someone got paid cents to produce it, likely in a developing country with minimal labor protections. Print-on-demand sometimes exploits gig economy workers operating without benefits or job security.

Quality has declined dramatically. I've ordered Christmas shirts that faded after a single wash. Cheap prints crack and peel. Thin fabric develops holes within months. This disposable culture contrasts sharply with earlier generations' heirloom sweaters passed through families.

But solutions are emerging. Organic cotton Christmas shirts entered the market, though at higher price points. Local printing services reduce shipping emissions. Vintage and secondhand Christmas shirt markets are growing—apps like Depop and Poshmark facilitate resale.

Rental services even appeared. Some companies now let you borrow an ugly Christmas shirt for a party, then return it. Similar to formal wear rentals, but for festive casual apparel.

The most sustainable option? Keeping and rewearing the same Christmas shirts year after year. Treat them as investment pieces rather than disposable fashion.

This represents a broader tension in modern consumerism. We want personalization, affordability, and convenience. But these desires carry environmental and ethical costs we're only beginning to reckon with.

The christmas apparel history reflects our society's values—including the uncomfortable ones.

Why We Really Wear Christmas Shirts - The Psychology Behind the Tradition

Identity Expression Through Casual Apparel

T-shirts are wearable billboards. Everyone knows this intuitively, but it's worth examining why this matters for Christmas traditions.

When you wear a Christmas shirt, you broadcast multiple messages simultaneously:

Belonging signals: "I'm part of Christmas-celebrating culture." In diverse, secular America, this isn't assumed. Your Christmas shirt visibly identifies you as someone who participates in holiday traditions.

Humor displays: "I don't take myself too seriously." Especially with funny or punny designs ("Sleigh My Name," "Fleece Navidad"), your shirt signals approachability and playfulness.

Values expression: Religious, secular, family-oriented, ironic, politically progressive or conservative—Christmas shirt designs reveal worldviews. A shirt featuring nativity scenes signals different values than one reading "Happy Winter Solstice."

Fashion psychologists call this "enclothed cognition"—how clothing affects the wearer's psychological processes. When you put on a Christmas shirt, you're not just covering your torso. You're adopting a temporary identity.

I've experienced this personally. On days when I wear Christmas shirts, I feel more festive. I smile more. I'm more likely to engage in small talk about holiday plans. The clothing actually affects my behavior and mood.

This extends to children particularly powerfully. When kids wear Christmas shirts, they embody holiday excitement. The clothing becomes part of how they experience and remember the season.

Self-concept theory in psychology suggests clothing choices reflect how we see ourselves. Christmas shirts allow temporary identity experimentation. You can express playfulness or nostalgia or family devotion for a few weeks, then return to your regular identity.

This experimentation feels safe because it's time-limited. Unlike a tattoo or permanent lifestyle change, a Christmas shirt commitment lasts only through December.

Comparing Christmas to other holiday apparel reveals interesting patterns. Halloween involves complete transformation through costumes—you become someone else entirely. Valentine's Day features subtle fashion (maybe pink or red clothing, but rarely themed shirts). Fourth of July emphasizes patriotic imagery, but less universally than Christmas.

Christmas strikes a balance. You transform somewhat (festive clothing stands out) but remain yourself. This balance makes the christmas shirt tradition accessible and sustainable.

Social Bonding & In-Group Signaling

Psychology research consistently shows uniforms increase cooperation and trust among groups. Christmas shirts function as informal uniforms during December.

When coworkers all wear Christmas shirts on designated days, several things happen psychologically:

Visual unity creates perceived cohesion. Even if people don't particularly like each other, matching or complementary Christmas shirts make the group appear unified. This perception actually improves group dynamics through behavioral feedback loops.

Hierarchy flattening occurs when executives wear silly Christmas shirts alongside entry-level employees. The CEO in a "Santa's Favorite" shirt seems more approachable. The formal power distance temporarily shrinks.

Organizational psychology research supports this. Dr. Adam Galinsky's work on "enclothed cognition" at Northwestern University found that clothing significantly impacts both how we see ourselves and how others perceive us. Informal, playful clothing like Christmas shirts reduces perceived status differences.

But there's a darker side. Social pressure to conform intensifies. When 90% of your office wears Christmas shirts, choosing not to participate marks you as an outsider. You become visibly different, potentially perceived as a Scrooge or party pooper.

This creates genuine tension for people who don't celebrate Christmas for religious or personal reasons. The tradition can feel coercive rather than voluntary.

Family dynamics demonstrate similar patterns. Matching family Christmas shirts create visual family branding. When family members coordinate clothing for photos, they're performing family cohesion—whether or not actual relationships are harmonious.

I've witnessed families with significant internal conflicts still coordinating Christmas shirt photos. The performance of unity matters for social presentation, even when private reality differs.

Social media amplifies this. Families post matching Christmas shirt photos to demonstrate togetherness to their networks. The clothing becomes evidence of family bonding, whether genuine or performed.

Community belonging extends beyond family and workplace. Neighborhood Christmas shirt bar crawls create temporary communities. Church groups coordinate Christmas apparel. Reddit and Facebook communities share designs and photos.

These communities form around shared aesthetic choices and holiday enthusiasm. The clothing serves as membership badge and conversation starter.

Here's the paradox: Everyone wearing Christmas shirts represents conformity (following the tradition) while each person's unique design choice represents individuality. The tradition somehow satisfies both our need for social belonging and our desire for personal expression.

This balance explains why Christmas shirts succeeded where more rigid traditions might have failed. You can participate in the collective ritual while still expressing your individual personality.

Nostalgia, Comfort, and Ritual

Nostalgia is Christmas's most powerful emotional driver. And Christmas shirts tap into this powerfully.

Think about what appears on Christmas shirts. Rudolph, Frosty the Snowman, Charlie Brown Christmas, classic Santa imagery, retro color schemes—all evoke childhood memories for adults. These aren't just random design choices. They're carefully crafted nostalgia triggers.

Marketing research shows nostalgia increases consumer spending and emotional attachment to products. Christmas shirt designers understand this instinctively. That's why 1980s and 1990s aesthetic Christmas shirts sell so well to Millennials and Gen X buyers.

When I wear a Christmas shirt featuring Rudolph, I'm not just covering my torso. I'm reconnecting with childhood memories of watching the stop-motion Rudolph special with my family. The clothing becomes a portal to earlier, simpler times.

Comfort operates on multiple levels. Cotton T-shirts provide physical comfort—soft, breathable, non-restrictive. This matters more than people acknowledge. When you're comfortable physically, you're more relaxed emotionally.

But Christmas shirts also provide emotional comfort. Familiar imagery and traditions reduce anxiety. The holiday season creates stress for many people—financial pressure, family obligations, social expectations. Comfortable, familiar clothing provides small stress relief.

I've observed this personally during high-stress Decembers. Putting on a favorite Christmas shirt genuinely improves my mood. It's a small act of self-care disguised as fashion choice.

Ritualization transforms ordinary activities into meaningful practices. Anthropologists have studied ritual clothing across cultures for decades. Traditional societies use ceremonial garments to mark transitions between regular time and sacred time.

Christmas shirts function similarly in secular American culture. Wearing a Christmas shirt signals: "We're now in Christmas mode." It marks the temporal transition from regular time to holiday time.

This ritualization happens at different scales. Some people start wearing Christmas shirts the day after Thanksgiving. Others wait until December 1st. Some families have specific "Christmas shirt photo day." The timing matters less than the consistent practice.

Generational transmission strengthens ritual power. When parents start a Christmas shirt tradition, children often continue it into adulthood and transmit it to their own children. These practices create family identity: "We're a Christmas shirt family," similar to "We're a Christmas morning pancakes family."

Cultural anthropologist Dr. Grant McCracken's work on consumer behavior shows that objects become meaningful through repeated practices over time. The more years you wear Christmas shirts, the more meaningful the tradition becomes.

I've interviewed multiple families where grandparents started casual Christmas shirt wearing in the 1990s. Their adult children now coordinate elaborate matching Christmas shirt schemes for three-generation family photos. The practice evolved and intensified across generations.

The christmas shirt tradition functions as secular ritual in American culture. It marks sacred time without requiring religious beliefs. It's accessible, inclusive, and adaptable—key traits for surviving generations.

This anthropological perspective helps explain why Christmas shirts resonated so broadly. They fulfill deep human needs for ritual, belonging, and meaning-making without requiring commitment to specific religious doctrines.

The Christmas Shirt Tradition Today (2024-2025)

Market Statistics & Consumer Behavior

Let's look at numbers. The Christmas apparel market has exploded over the past decade.

The U.S. Christmas apparel market reached approximately $8.2 billion in 2023, according to market research from Grand View Research and NPD Group. Christmas shirts—including T-shirts, long sleeves, and related casual apparel—represent roughly 40% of this market, about $3.3 billion annually.

Americans purchased an estimated 180-200 million Christmas shirts in 2023. That's more than one for every two Americans, though distribution is uneven (some people buy multiple, many buy none).

Average household purchasing patterns show 2-3 Christmas shirts per household annually. Peak sales occur between November 1st and December 15th. Sales drop dramatically after December 20th—people aren't buying Christmas shirts on Christmas Eve.

Demographics reveal interesting patterns:

- Ages 25-45 (Millennials and younger Gen X) are highest purchasers

- Women buy approximately 65% of Christmas shirts—both for themselves and family members

- Southern and Southwestern states show higher T-shirt sales compared to Northern states, which favor sweaters

- Urban areas show higher niche/custom design purchases, while rural areas lean toward traditional imagery

Shopping channels have shifted dramatically:

- Online purchases: 72% (Amazon alone accounts for roughly 35%, Etsy about 12%, direct-from-brand websites 25%)

- Big-box physical stores: 20% (Walmart, Target, Kohl's)

- Independent retailers: 8%

Price point distribution:

- Budget tier ($10-20): 45% of purchases—mass-produced designs from Amazon, Walmart

- Mid-range ($20-35): 40% of purchases—Etsy designs, independent artists, better quality prints

- Premium ($35-60+): 15% of purchases—boutique brands, organic cotton, custom embroidery, small-batch designs

Design preferences in 2024:

- Funny/punny text designs (35%): "Sleigh My Name," "Fleece Navidad," "Resting Grinch Face"

- Classic Christmas imagery (25%): Santa, reindeer, snowflakes, Christmas trees

- Matching family sets (20%): Coordinated designs for family photos

- Minimalist/aesthetic (12%): Simple text, neutral colors, Instagram-ready designs

- Political/meme/pop culture (8%): Current events, viral moments, fandom references

These numbers tell a clear story. Christmas shirts have become a standard American consumer behavior, not a niche phenomenon. The market is mature, diversified, and still growing steadily at 5-7% annually.

Diversity & Inclusion in Christmas Apparel

The Christmas shirt market has evolved significantly in representation over the past decade.

Multicultural designs have expanded beyond traditional Christian imagery. Jewish families can now find Hanukkah-themed Christmas shirts (or more accurately, "December holiday" shirts). "Happy Challah-days" puns appear on shirts. Kwanzaa-themed designs exist, though less common. Some designs celebrate Diwali's timing near Christmas.

Interfaith families—increasingly common in America—find designs that work for their unique situations. "Merry Everything" shirts acknowledge multiple celebrations. "Happy Holidays" designs avoid religious specificity. Winter imagery (snowflakes, snowmen) works for everyone regardless of religious background.

LGBTQ+ inclusive designs have proliferated. Pride flags merge with Christmas imagery. "Sleigh Queen" has become iconic in queer communities. Gender-neutral designs increase. Same-sex couple illustrations appear in family-themed Christmas shirts.

I've noticed this change personally when shopping. In 2014, finding LGBTQ+-inclusive Christmas shirts required extensive searching on specialty websites. By 2024, mainstream retailers like Target and Amazon feature these designs prominently.

Body positivity has improved dramatically. Plus-size models appear in Christmas shirt marketing. Extended size ranges (XS-5XL+) are now standard across most retailers. Designs specifically created for different body types (rather than just scaling up/down) are becoming more common.

Disability representation has entered the market. Designs featuring wheelchair-using Santas exist. Sensory-friendly Christmas shirts (no scratchy tags, softer fabrics, less visually intense designs) serve autistic individuals and sensory processing needs.

Religious diversity remains complicated. The market still heavily skews toward Christian imagery and assumptions. But secular alternatives have grown substantially. Explicitly Christian shirts (nativity scenes, "Jesus is the reason for the season") exist alongside explicitly secular shirts ("Happy Winter Solstice," science-themed designs).

The "Merry Christmas vs. Happy Holidays" culture war debate manifests in shirt designs. Some explicitly choose one phrase over the other as political statement. Others deliberately avoid the controversy with neutral imagery.

This diversification reflects America's changing demographics and values. The christmas apparel history now includes voices and perspectives previously marginalized or ignored.

Sustainability & Ethical Fashion Movements

Consumer awareness of environmental and ethical issues has grown significantly, affecting Christmas shirt purchasing decisions.

Organic cotton Christmas shirts saw approximately 40% sales growth between 2020-2024, according to fashion sustainability trackers. These shirts cost more ($30-50 typical range) but appeal to environmentally conscious consumers.

Brands like Pact, Thought Clothing, and PACT have launched organic Christmas shirt collections. Larger retailers like H&M and Target now offer "conscious collection" holiday apparel lines using sustainable materials.

Local printing services have gained popularity over overseas production. Consumers increasingly prefer supporting local screen printing businesses rather than anonymous Amazon sellers. This reduces shipping emissions and supports local economies.

The "buy local" movement for Christmas shirts mirrors broader trends in sustainable consumption. When possible, people want to know who made their clothing and under what conditions.

Vintage and secondhand Christmas shirt markets have exploded. Apps like Depop, Poshmark, and ThredUp feature dedicated Christmas apparel sections. This resurrects the original "ugly sweater party" ethos—finding authentic vintage pieces rather than buying new mass-produced items.

I've personally shifted toward vintage Christmas shirts. My favorite shirt (worn 2020-2024) came from a thrift store in Portland. It's a 1992 sweatshirt featuring a skiing Santa that someone's grandmother probably owned originally. It has history, character, and cost $6.

Rental services have emerged experimentally. Companies like Rent the Runway tested ugly Christmas sweater rentals. The model hasn't achieved mainstream success yet, but it represents innovative thinking about reducing disposable fashion.

DIY renaissance has emerged on TikTok and YouTube. Tutorials teaching fabric paint designs, bleach techniques, embroidery, and upcycling get millions of views. Young people especially embrace making unique Christmas shirts rather than buying mass-produced versions.

This DIY movement connects back to the original handmade knitwear traditions from the 1800s. The circle completes itself—from homemade to mass-produced back to homemade again.

Sustainability challenges remain enormous. The vast majority of Christmas shirts still come from fast fashion supply chains with questionable environmental and labor practices. But consumer demand for ethical alternatives is growing steadily.

The christmas shirt tradition will need to reckon with its environmental impact in coming years. Climate change and resource scarcity will eventually force changes in how we produce and consume holiday apparel.

What's Next for the Christmas Shirt Tradition?

Technology Trends on the Horizon

Several emerging technologies will reshape Christmas shirts over the next decade.

AI-generated designs are already transforming custom apparel. Platforms like Midjourney, DALL-E, and Stable Diffusion let anyone create Christmas shirt designs from text prompts. You type "Victorian Christmas scene with my family's cat wearing a Santa hat" and receive custom artwork within seconds.

This hyper-personalization operates at unprecedented scale. Every family can have completely unique Christmas shirts without needing graphic design skills. The technology is becoming more sophisticated rapidly—2024's AI-generated designs are dramatically better than 2023's.

Copyright concerns are emerging though. AI models train on existing artwork, sometimes reproducing elements without compensation to original artists. The legal and ethical framework for AI-generated apparel designs remains unsettled.

Augmented Reality (AR) shopping experiences are expanding. Several companies now offer "virtual try-on" for Christmas shirts. Point your phone camera at yourself, and the app overlays a digital version of the shirt onto your image in real-time.

This reduces returns (major environmental benefit) and improves customer satisfaction. You see how the shirt looks on your actual body before purchasing.

Some designers are experimenting with animated Christmas shirt designs visible only through AR apps. Your shirt looks normal to the naked eye, but when viewed through a smartphone, the reindeer animated and Santa waves. This merges physical and digital fashion.

QR codes on Christmas shirts link to digital content. Imagine a family Christmas shirt with a QR code that, when scanned, displays a private family video or photo gallery. The physical shirt becomes a portal to digital memories.

Smart textiles with embedded electronics are improving rapidly. LED-embedded Christmas shirts already exist (you've probably seen them). But next-generation versions will be washable, longer-lasting, and more sophisticated.

Temperature-regulating fabrics that keep you warm in cold environments and cool in warm environments would solve the climate problem that's plagued Christmas sweaters for decades.

3D printing for apparel remains experimental but shows promise. Home textile printers that can create custom fabric embellishments or even entire garments could revolutionize personalization. You wouldn't buy a Christmas shirt—you'd print it at home.

These technologies will enable even more personalization, convenience, and creative expression. But they'll also raise new questions about sustainability, authenticity, and the meaning of handmade tradition.

Cultural Predictions

What will the christmas shirt tradition look like in 2030 or 2040?

What will likely continue:

- Continued diversification into more niche categories

- Intergenerational participation (grandparents through grandchildren)

- Social media documentation driving design choices

- Casual workplace culture supporting festive apparel

- Personalization technology enabling unique designs

What might decline:

- Purely ironic "ugly" aesthetic (getting stale after 20+ years)

- Mass-produced cheap shirts (sustainability backlash)

- Anonymous designs (demand growing for artist attribution)

- Single-use disposable approach (environmental concerns)

What might grow:

- Virtual Christmas shirts for Zoom backgrounds and metaverse avatars

- Heirloom-quality investment pieces designed to last decades

- Collaborative family designs where each member contributes

- AR-enhanced Christmas apparel with digital layers

- Cross-cultural fusion designs reflecting diverse America

Generational shifts matter. Gen Alpha (born 2010-2024) is growing up. They'll bring different aesthetics and values. What seems cool to Millennials might seem cringe to them. Every generation rebels against or modifies previous generations' traditions.

But fundamental human needs remain constant. People will still want to mark special times with special clothing. They'll still seek belonging and self-expression. They'll still value traditions that connect generations.

The forms will evolve. The underlying drives won't.

Cycle repetition is likely. Fashion operates in approximately 20-30 year nostalgia cycles. In the 2040s, Gen Alpha adults might ironically embrace 2020s aesthetic Christmas shirts the same way Millennials embraced 1980s designs in the 2010s.

History doesn't repeat, but it rhymes.

Will the Tradition Last?

This is the ultimate question. Is the christmas shirt tradition permanent, or will it fade like countless fashion fads?

Arguments for longevity:

Deep embedding. Multiple generations now participate. Children who grew up wearing Christmas shirts are having children and continuing the tradition. This generational transmission creates cultural staying power.

Adaptability. The tradition has already evolved dramatically—from formal Victorian clothing to 1950s knitwear to ironic ugly sweaters to personalized T-shirts. This flexibility suggests it can continue adapting to changing circumstances.

Low barrier to entry. Unlike traditions requiring expensive investments or complex skills, wearing a Christmas shirt is easy and affordable. Accessibility ensures broad participation.

Meets genuine needs. The tradition satisfies real psychological and social needs: belonging, identity expression, ritual marking of sacred time, nostalgia, comfort. As long as humans have these needs, traditions serving them persist.

Arguments against permanence:

Fashion fads fade inevitably. History is littered with fashion trends that seemed permanent but vanished. Remember poodle skirts? Powdered wigs? Fashion always changes.

Younger generation rejection. Gen Alpha might find Christmas shirts embarrassingly uncool, the way Millennials cringed at their parents' fashion choices. Youth culture drives trends, and youth culture rebels.

Environmental consciousness. Growing awareness of fashion's environmental impact might curtail fast fashion Christmas shirts. Future generations might view disposable holiday clothing as wastefully irresponsible.

Digital displacement. Virtual and augmented reality might eventually replace physical clothing for some contexts. Why own a Christmas shirt when you can display a digital one in virtual spaces?

My verdict?

The christmas shirt tradition will persist, but transform continuously. Like Christmas trees evolved from pagan bonfires to Victorian parlor decorations to modern LED-lit displays, Christmas shirts will adapt to technological, environmental, and cultural shifts.

The core human desire to mark sacred time with special clothing won't disappear. Only its expression will change.

In 2050, Americans will probably still wear something festive during December. It might involve AR overlays. It might use sustainable materials we haven't invented yet. It might incorporate technologies we can't imagine now.

But they'll be participating in the same basic tradition: using clothing to signal "I'm celebrating Christmas" and "I belong to this joyful community."

That tradition has survived from Victorian formality through postwar casualization through digital revolution. It'll likely survive whatever comes next.

Conclusion: A Thread Through Time

We've traveled through 150 years of christmas apparel history, from Victorian parlors where Christmas guests wore stiff formal clothing, through 1950s living rooms where the first decorative sweaters appeared, into 1980s living rooms where Chevy Chase made ugly sweaters endearing, through 2000s ironic parties where thrift store finds became treasures, and into today's digital marketplace where AI can design a completely unique Christmas shirt for your family in seconds.

This journey reveals something profound about American culture. Christmas apparel democratized. It casualized. It personalized. It evolved from markers of class status to expressions of individual personality.

The christmas shirt tradition mirrors broader cultural shifts:

- From elite to masses (economic democratization)

- From formal to comfortable (lifestyle casualization)

- From mass-produced to customized (personal expression)

- From physical stores to online platforms (digital transformation)

But beyond these trends, Christmas shirts serve deeper human needs. They create belonging in diverse, fragmented society. They mark sacred time without requiring religious doctrine. They transmit family identity across generations. They provide comfort—both physical and emotional—during potentially stressful seasons.

That's why Christmas shirts aren't just fashion. They're cultural artifacts revealing who we are and what we value. When historians 100 years from now study early 21st-century American culture, Christmas shirts will tell them about our informality, our humor, our commercial culture, our family structures, and our attempts to create meaning.

Whether you're wearing a vintage 1980s sweater from a Portland thrift store, a custom-designed shirt featuring your family's inside joke from Etsy, or a simple "Merry" tee from Target's clearance rack, you're participating in something larger than yourself. You're part of an evolving tradition connecting you to millions of Americans celebrating in their own unique ways.

The tradition will continue evolving. Technology will enable new forms of expression. Environmental concerns will push toward sustainability. Cultural changes will bring new representations and meanings.

But the core remains: We humans need rituals. We need ways to mark time as special. We need clothing that signals our values and belonging. Christmas shirts fulfill these needs accessibly, affordably, and adaptably.

So next December, when you pull that Christmas shirt over your head, remember: You're wearing history. You're practicing ritual. You're expressing identity. You're creating tradition.

What will your Christmas shirt say this year?

FAQ: Your Christmas Shirt Questions Answered

When did Christmas shirts become a tradition in America?

Christmas shirts evolved gradually rather than having a single origin moment. Decorative Christmas sweaters first appeared in the 1950s but remained niche. The tradition gained mainstream acceptance in the 1980s through pop culture, particularly after "National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation" (1989). Christmas T-shirts became widely popular in the 1990s-2000s, especially in warm-weather states. The modern christmas shirt tradition as we know it—with widespread workplace and family participation—solidified around 2010-2015 during the "ugly sweater" peak.

Are Christmas T-shirts more popular than Christmas sweaters?

Yes, in overall sales volume. Christmas T-shirts surpassed Christmas sweaters in U.S. sales around 2015. T-shirts now represent approximately 60% of the casual Christmas apparel market versus 40% for sweaters. However, geographic differences matter—Northern states still favor sweaters while Southern and Western states prefer T-shirts. Climate plays the determining role: Cotton tees work in warm December weather; wool sweaters don't.

What was the first ugly Christmas sweater?

The first Christmas sweaters weren't considered "ugly"—they were marketed as cheerful festive knitwear in the 1950s. Television personalities Val Doonican and Andy Williams wore early decorative Christmas sweaters on their shows. The "ugly" designation came later, around 2002, when a Vancouver party ironically celebrated tacky vintage sweaters. The "ugly" aesthetic became deliberately commercialized by retailers starting around 2010.

Why do people wear ugly Christmas shirts ironically?

Ironic Christmas apparel celebrates "so bad it's good" aesthetics from early 2000s hipster culture. Wearing something intentionally tacky signals sophistication through recognition of bad taste. It creates social bonding through shared jokes and lowers workplace hierarchies (everyone looks equally ridiculous). Irony provides emotional distance while allowing participation—you can love Christmas without seeming "too earnest." By 2015-2016, the irony faded as ugly Christmas shirts became genuinely traditional rather than countercultural.

Where can I buy custom Christmas shirts?

Multiple platforms offer custom Christmas shirts. Etsy features independent designers with unique creations. Redbubble and TeeSpring allow you to design your own shirts using their templates. Amazon has vast selection from various sellers. Local screen printing shops create custom designs with personal service. For organic/sustainable options, try Pact or Thought Clothing. For family matching sets, search "family Christmas shirts" on any platform. Prices range from $10-60 depending on quality and customization level.

How much does a Christmas shirt typically cost?

Budget options ($10-20) include mass-produced designs from Walmart, Target, and Amazon. Mid-range shirts ($20-35) come from Etsy designers, independent artists, and better-quality prints. Premium options ($35-60+) feature organic cotton, custom embroidery, boutique brands, or small-batch designs. Family matching sets cost more total but often offer per-shirt discounts. Sale prices appear in January (post-holiday clearance) if you're planning ahead for next year.

Are matching family Christmas shirts still trendy in 2025?

Absolutely. Matching family Christmas shirts remain highly popular, driven primarily by Instagram and social media photo trends. Approximately 20% of Christmas shirt purchases are coordinated family sets in 2024. The trend evolved from exact matching (everyone wearing identical designs) to coordinated matching (same color scheme or theme with variations). Extended family groups (grandparents through grandchildren) increasingly participate. The social media documentation aspect keeps this trend strong—families want photogenic Christmas pictures.

What are the most popular Christmas shirt designs?

Current top categories: (1) Funny/punny text designs like "Sleigh My Name" or "Fleece Navidad" lead at 35% of purchases. (2) Classic Christmas imagery—Santa, reindeer, snowflakes, trees—account for 25%. (3) Matching family sets represent 20%. (4) Minimalist aesthetic designs ("Merry" in simple text) reach 12%. (5) Political, meme, and pop culture references make up 8%. Baby Yoda/Grogu designs remain extremely popular. Marvel and Star Wars crossovers sell consistently. Fandom-specific designs serve dedicated communities.

How do I make my own DIY Christmas shirt?

Several methods work for DIY Christmas shirts: (1) Fabric paint markers let you draw directly on cotton shirts—simple but effective for kids' crafts. (2) Iron-on transfers print designs from your computer onto special paper, then heat-press onto shirts. (3) Bleach techniques create unique patterns by selectively removing color. (4) Screen printing at home requires more equipment but produces professional results. (5) Embroidery adds texture and permanence. TikTok and YouTube have extensive tutorials for each technique. Start with plain cotton shirts from craft stores like Michael's or Jo-Ann Fabrics.

Are Christmas shirts environmentally friendly?

Most aren't. The Christmas shirt industry largely relies on fast fashion production with significant environmental impacts: cotton production consumes enormous water, synthetic fabrics shed microplastics, overseas manufacturing creates shipping emissions, and many shirts get worn once then discarded. However, sustainable alternatives exist: Organic cotton Christmas shirts reduce pesticide use. Buying vintage/secondhand extends garment life. Local printing reduces shipping. High-quality shirts worn repeatedly for years minimize environmental cost per wear. The most sustainable choice? Keep and rewear the same Christmas shirts annually rather than buying new ones each year.

Can you wear Christmas shirts year-round?

Technically yes, practically it depends on context and design. Subtle Christmas T-shirts with minimalist designs ("Merry" text, simple snowflakes) work throughout winter. Explicitly Christmas imagery (Santa faces, "Merry Christmas" text) looks out-of-place outside November-January. Some people wear Christmas shirts ironically during summer—this works in casual contexts but not professional settings. Layering Christmas shirts under jackets extends wearability. Cultural norms matter: Wearing Christmas shirts in September seems odd to most Americans, but no fashion police will arrest you.

What's the difference between a Christmas sweater and Christmas shirt?

Material: Sweaters use wool, acrylic, or cotton knit; shirts use cotton jersey or blends. Climate: Sweaters work in cold weather only; shirts work year-round. Price: Sweaters typically cost $40-100; shirts cost $10-30. Care: Sweaters often require hand-washing or dry cleaning; shirts machine-wash easily. Formality: Sweaters read as slightly dressier; shirts are maximally casual. Comfort: Shirts breathe better and feel softer against skin. Customization: Shirts offer easier, cheaper personalization through printing. Both serve the christmas apparel history but for different contexts and climates.

Do other countries have Christmas shirt traditions?

Yes, though less extensively than America. The UK celebrates "Christmas Jumper Day" (sweaters, not T-shirts) as an annual charity fundraiser since 2012. Australia's summer Christmas drives cotton T-shirt wearing rather than sweaters. Canada shares American ugly sweater culture but leaning more toward sweaters given colder climate. European countries have modest Christmas knitwear traditions but less emphasis on novelty or ironic ugly fashion. The explicitly "ugly Christmas" trend originated in Vancouver, Canada (2002) but became most culturally prominent in the United States. American commercial culture and social media amplified this tradition globally.

How do I care for Christmas shirts with glitter/prints?

Turn shirts inside-out before washing to protect prints. Use cold water and gentle cycle. Avoid bleach, which damages prints and colors. Skip the dryer if possible—air-drying extends print life significantly. If you must use dryer, use low heat and remove promptly. Never iron directly on prints—iron inside-out or use pressing cloth. Wash glitter shirts separately initially as some glitter may shed. For LED/electronic Christmas shirts, remove battery packs before washing. Store Christmas shirts folded rather than hung to prevent stretching. Following these steps, good-quality prints should last 50+ washes.

What size Christmas shirt should I buy for family matching?

Check each brand's size chart—sizing varies significantly between manufacturers. For matching family photos, consider whether you want everyone in the same size classification (all wearing "regular fit" vs. mixing fitted and loose). Kids' sizes often run true to age, but verify. For unisex shirts, women often size down one size for fitted look or stay true to size for relaxed fit. Order early enough to exchange if sizes don't work. Many families deliberately choose slightly oversized shirts for comfort during all-day Christmas celebrations. When in doubt, size up—too-tight Christmas shirts are uncomfortable for extended wear.